Despite the innumerable advantages that rapid industrialization has brought into our lives, it is susceptible to avoid the fading fates of some of our cultural heritages at the same time. When technology develops unstoppably, people tend to treasure handmade crafts, traditional songs, and dance less - they no longer realize the importance of these values.

As a Vietnamese and also as a Gen Z, I perceive spreading and preserving my culture, my roots, and my identity as my responsibility. Hence, in this article, I would love to share about Dó paper - a famous Vietnamese handicraft on the verge of disappearing a few years ago. Thanks to local, international artists and conservationists, the craft is now being revived.

Let us slide into your dms 🥰

Get notified of top trending articles like this one every week! (we won't spam you)I. Introduction of Dó Paper

1. Material and process

Dó papers are produced from the bark of the Dó tree through a manual process passed down through generations in some craft villages in Vietnam. They are used for painting in Vietnamese folk art, especially to make paper for Dong Ho paintings, or to keep important documents from the past. Due to the characteristics of the Dó tree, its products are known for their durability over time.

Research at the production facilities of Dó paper in Vietnam shows there is no chemical effect to create acid in the paper. The bark is cooked and soaked in lime water for three months, peeled off the black bark, pounded with a mortar and pestle, and then used the mucilage from the sardines to create a sticky mixture.

When rolling the paper, the worker uses a sickle (molded with a bamboo curtain or thick copper wire) to swing back and forth in the flour bath. The layer of dough on the sickle is the Dó paper after the end of pressing, drying, compacting, or flattening. The fibers clump together, like a multi-layered spider web, forming a sheet of dó paper.

Such curing has made paper porous. After the whole process, the artisan lets them dry in the sunlight.

2. History

The traditional village of producing Dó paper in Vietnam has a long history. Dó, an excellent paper with special quality criteria that other ordinary papers do not have, is a product imbued with Vietnamese culture. The birth, development, and perfection of the craft of making dó and paper-making are closely associated with the nation, with thousands of years of civilization, vividly demonstrating creative labor ability and necessary virtues. the hard work of many generations of artisans and craftspeople in traditional craft villages.

The survey in Nghia Do ward and the stories of the elders declared that the Lai family in Nghia Do village started making paper for the kings from the Le-Trinh dynasty (around 1545–1787), and then then developed to the present for several hundred years. However, there are not many traces of papercraft remaining now, since most of the experienced artisans have already passed away.

3. The Application

- Book printing: In the past, Vietnamese people printed using paper printing technology on wooden boards. Nowadays, poet Nguyen Duy uses inkjet printers to print on Dó paper.

- Notes: Suitable for brush use.

- Folk painting, calligraphy

- Decoration

- Moisture-proof paper

- Fan, earring

- Producing soundproofing, heat-insulating panels, loudspeaker diaphragms

Take the Quiz: What Color Palette Is Your Soul Made Of?

Discover your true colors with this quiz!

II. The effort to revive Dó paper

One of the most noticeable organizations in the effort to revive Dó Paper is the Zó Project. Ms. Tran Hong Nhung, the enterprise's creator, was first inspired by her passion for Dó paper.

Zó is a vibrant and energetic team that aims to infuse traditional values into modern culture. The revenues are then given back to the paper-making community in order to provide employment opportunities and a steady source of income for the ethnic minority hamlets in Vietnam's Northern region.

We have been endeavoring to work alongside traditional papermakers and revolutionize what they do for contemporary functions like earrings, calligraphy, postcards, and lamp covers. Not only creating creative practical productions, but Zó project also organizes workshops or paper-making tours for tourists.

With the desire to spread Dó paper to the world, Ms. Tran Hong Nhung, as well as her team, always seek more and more collaboration with both domestic and international artists, so in the near future, the Dó paper exhibition or lookbook will be debuted.

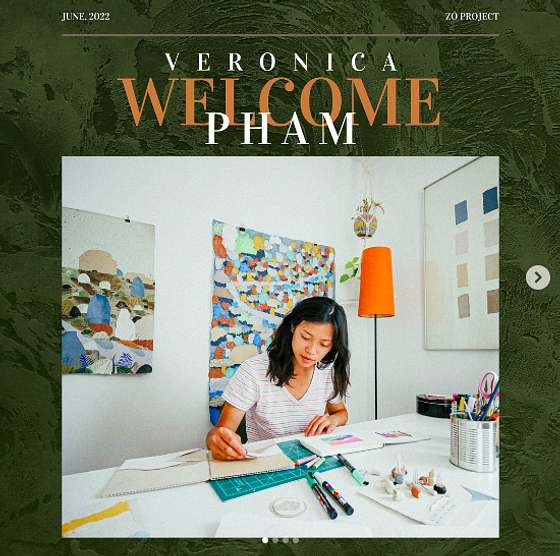

Below is the interview I did with Veronica Pham, a Vietnamese-American artist in residence. She loves the feeling of making handmade paper, being able to make her own materials, and knowing its origin and the sustainability behind the materials she uses.

Question 1: What part did you like the most about the paper-making trip?

I enjoyed learning the traditional seo techniques and meeting each papermaker from the different regions. Having previously learned Western and Japanese pulling techniques for papermaking, learning the seo technique was the most rewarding.

It was very important to me to be able to note the differences and similarities of how Vietnamese papermaking techniques differ from other papermaking techniques. Noting these differences and similarities helped me understand how traditional papermaking in Vietnam should be recognized globally.

Question 2: Why did you choose Zó Project as an art station?

I chose the Zó project because Zó is the only project that is actively connected with papermaking communities to celebrate traditional papermaking in Vietnam. With little to no documentation of hand papermaking techniques in the US, Zó was the only social enterprise that was actively focusing on craft preservation for papermaking traditions in Vietnam.

Question 3: What did you learn after experiencing making paper with Zó?

I learned so much! Along with learning the seo technique for making handmade paper, I learned a lot about natural dying with the local materials in Vietnam. From colors from cẩm hồng to producing a pinkish orange, to the deep history of indigo dying in Vietnam, it's been an amazing learning experience. It inspires me to continue experimenting with natural materials for dying pulp.

Question 4: How do you feel about Vietnamese artists?

The artists in Vietnam have an incredible resiliency in their craft. From woodblock printers to calligraphy artists to traditional makers, I feel that artists in Vietnam have become integral to keeping the history of the ancient craft alive. Many artists have kept craft traditions going through their own work and I see the importance of bridging traditions to contemporary art.

I feel overwhelmed learning about Vietnamese traditions and the road that many artists are taking to evolve traditions in keeping and transforming them. There are so many talented artists in Vietnam!

Question 5: Did Zó change your perspective on handmade paper?

My experience at Zó confirmed how important handmade paper is in Vietnam. Having a deep love for papermaking and materials, I already felt a deep desire to learn. Zó has taught me that there are abundant ethnic communities practicing traditional papermaking that is unique to their local region and that it isn't confined to just traditional dó papermaking.

Conclusion

Compared to a few years ago, Dó paper's position in the world has improved substantially due to people's acknowledgment of traditional values and heritage. Indeed, it is still up to us, the younger generation, to both preserve our identity and embrace the cultural diversity in the world. The revival of Dó paper from Vietnam is a clear demonstration of the connection between the past and the present, in which the key is to create the new for the old.

For more visual information, please watch this video by Business Insider.